Because we were in Eugene anyway for the Festival of Bands, my wife and I took a couple of hours that day to walk around the University of Oregon campus. My wife said she didn’t remember the campus, and so I showed her the main spots where I used to hang out. For example, Gerlinger Hall – where I just about had my eye gouged out by the tip of my instructor’s foil during a fencing class.

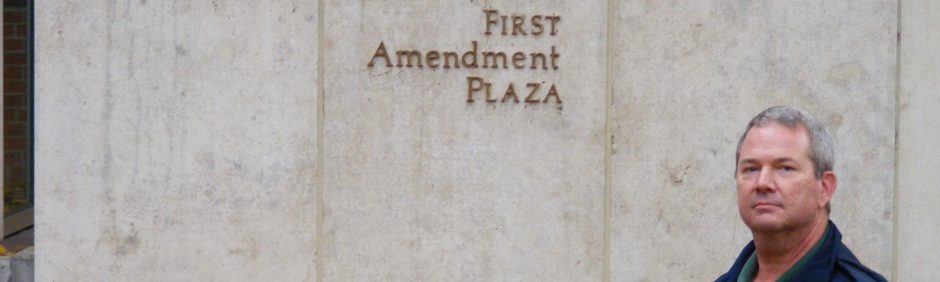

Since I graduated from U of O with a degree in journalism, the primary building for my studies was Allen Hall. As we walked around this building, and took some photos, my wife asked me to express my feelings about being there – how it felt to return after so many years. The first thing I told her was that it felt good to reflect on the fact that I completed it. In other words, I graduated. Many people who come here don’t. They don’t graduate; they don’t finish it.

When I focus on something, with a mild form of obsession, I get the job done. In fact, I

excelled in journalism school – at Allen Hall. I was featured in The National Deans’ List. I received two academic scholarships. I was awarded membership in Kappa Tau Alpha, the journalistic honor society. I remember that the professors occasionally read my work in front of the class.

This is still true in my life. When I exercise my concept of “controlled obsession,” I have a singular focus, and I get it done. I still feel this way when I’m in the middle of an article: conducting interviews, writing the draft, editing, rewriting, submitting the final draft.

Unfortunately, this pattern has not been consistent in my life. For instance: Ostensibly because my career goal at that point was nonprofit work with the church, I didn’t immediately pursue a journalism job when I graduated. Looking back, I’m not sure why I did it that way. My goal, however, was to use my journalism training in the nonprofit work.

As a result of a summer internship in Greece between my junior and senior years at U of O, I realized that the need for my skills and training was much greater outside of the USA than within it. I guess that’s one reason why I didn’t pursue a normal journalism job in the U.S.

But revisiting the campus – and Allen Hall – served as a reminder of my original goals and purpose. I realized that I had not been fulfilling my true potential, the one for which I came to U of O in the first place, and graduated.

Somebody once gave me some constructive criticism that was extremely valuable. He told me that I perceive myself to be successful because, like a high jumper, I make it across the bar. But nobody else is impressed because they can see that the bar is far too low.

He encouraged me to set the “bar” much higher in my life and career, because he was convinced that I would still make it across. I realized that I could and should set the bar much higher and, like Dick Fosbury, possibly set a record.

As I point out in the “sidebar” that follows this article, Dick Fosbury stills holds the Olympic and American high-jump records at 2.24 meters (or 7 feet, 4.25 inches). These records remain unbroken, which Fosbury set on October 20, 1968, at the Olympics in Mexico City, where he took the gold medal for high jump. He was able to achieve this success due to the unique, backward style he developed, which came to be called the “Fosbury Flop.”

In my own life, achieving that success is a matter of surmounting the fear of success and learned helplessness, as well as utilizing controlled obsession. These will be topics of future blog posts, as well as e-books, which will be free to download at this website.

For now, I am seeking to fulfill my original goals and purpose, which my personal criterion summarizes: Accomplishing what otherwise would not get done unless I do it. Part of achieving this might involve recognizing and embracing my own unique, backward style – like Dick Fosbury. And always setting the bar higher.

Lee Cuesta